I bought my first car at 16. It was an awesome little blue 4×4 (Bronco II). The test drive was perfect. I got to blast the radio and drive off-road through a sub-division under construction. Bouncing over piles of debris, I can still remember the exhilaration. Both the seller and I laughed the whole time. Only problem…he was still laughing two weeks later, while I was on the side of the highway spitting steam and pouring oil mixed with engine coolant. That 4×4 rusted in my driveway for another year before a neighbor bought it for less than 20% of what I paid.

Yeah…I skipped the inspection part. The car was just too much fun to think about that. And since it handled the test drive, what could really go wrong? I was going to be so freakin’ cool come fall in high school.

Tell me I’m the only one who’s ever dreamed of the stars and ended up on the bus.

Now that brings us to outcomes. Maybe you’ve been kicking the tires of a new education program and hoping it will generate great outcomes. Don’t get distracted by the shiny bits…there are three key things to inspect for every outcomes project (in descending order of importance and ascending order of coolness):

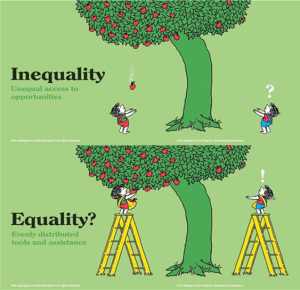

- Study design:the main concern here is “internal validity,” which refers to how well a study controls for the factors that could confound the relationship between the intervention and outcome (i.e., how do we know something else isn’t accelerating or breaking our path toward the desired outcome?). There are many threats to internal validity and, correspondingly, many distinct study designs to address them. One group pre-test/post-test is a study design, as is post-test only with nonequivalent groups (i.e., post-test administered to CME participants and a nonparticipant “control” group). There are about a dozen more options. You should understand why a particular study design was selected and what answers it can (and cannot) provide.

- Data collection:second to study design is data collection. The big deal here is “construct validity” (i.e., can the data collection tool measure what it claims?). Just because you want your survey or chart abstraction to measure a certain outcome, that doesn’t mean it actually will. Can you speak to the data that support the effectiveness of your tool in measuring its intention? If not, you should consider another option. Note: it is really fun to say “chart abstraction,” but it’s a data collection tool, not a study design. If your study design is flawed, you have to consider those challenges to internal validity plus any construct validity issues associated with your chart abstraction. The more issues you collect, the weaker your final argument regarding your desired outcome. An expensive study (e.g., chart review) does not guarantee a result of any importance, but it does sound good.

- Analysis:this is the shiny bit, and just like your parents told you, the least important. Remember Mom’s advice: if your friends don’t think you’re cool, then they aren’t really your friends. Well, think about study design and data collection as the “beauty on the inside” and analysis as a really groovy jacket and great hair. Oh yeah, it matters, but rather less so if it keeps getting you stuck on the highway. You may have heard that statisticians are nerds, but they’re the NASCAR drivers of the research community – and I’m here to tell you the car and pit crew are more important. In short, if your outcomes are all about analysis, they probably aren’t worth much.

Let’s continue the conversation about outcomes project inspections. Get in touch here.